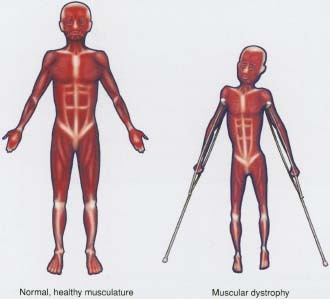

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a genetic disorder that gradually weakens the body's muscles. It's caused by incorrect or missing genetic information that prevents the body from making the proteins it needs to build and maintain healthy muscles.

A child who is diagnosed with MD gradually loses the ability to do things like walk, sit upright, breathe easily, and move the arms and hands. This increasing weakness can lead to other health problems.

There are several major forms of muscular dystrophy, which can affect a child's muscles in different levels of severity. In some cases, MD starts causing muscle problems in infancy, while in others, symptoms don't appear until adulthood.

There is no cure for MD, but researchers are quickly learning more about how to prevent and treat the condition. Doctors are also working on improving muscle and joint function, and slowing muscle deterioration so that kids, teens, and adults with MD can live as actively and independently as possible.

What Are the First Symptoms of Muscular Dystrophy?

Many kids with muscular dystrophy follow a normal pattern of development during their first few years of life.

But in time common symptoms begin to appear. A child who has MD may start to stumble, waddle, have difficulty going up stairs, and toe walk (walk on the toes without the heels hitting the floor). A child may start to struggle to get up from a sitting position or have a hard time pushing things, like a wagon or a tricycle. It is also common for a young child with MD to develop enlarged calf muscles, a condition called calf pseudohypertrophy, as muscle tissue is destroyed and replaced by fat.

How Is Muscular Dystrophy Diagnosed?

When a doctor first suspects that a child has muscular dystrophy, he or she probably will do a physical exam, take a family history, and ask about any problems - particularly those affecting the muscles - that the child might be experiencing.

In addition, the doctor may perform a series of tests to determine what type of MD a child may have and to rule out any other diseases that may be causing a problem. This might include a blood test to measure levels of serum creatine kinase, an enzyme that's released into the bloodstream when muscle fibers are deteriorating. Elevated levels of this enzyme indicate that something is causing muscle damage.

The doctor also may do a blood test to check a child's DNA for gene abnormalities, or a muscle biopsy to examine a muscle tissue sample for patterns of deterioration and abnormal levels of dystrophin, a protein that helps muscle cells keep their shape and length. Without dystrophin, the muscles break down.

Types of Muscular Dystrophy

The different types of muscular dystrophy affect different sets of muscles and result in different degrees of muscle weakness.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common and the most severe form of the disease. It affects about 1 out of every 3,500 boys. (Girls can carry the gene that causes the disease, but they usually have no symptoms.) This form of MD occurs because of a problem with the gene that makes dystrophin. Without this protein, the muscles break down and a child becomes weaker.

In cases of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, symptoms usually begin to appear around age 5, as the pelvic muscles begin to weaken. Most kids with this form of MD need to use a wheelchair by age 12. Over time, their muscles weaken in the shoulders, back, arms, and legs. Eventually, the respiratory muscles are affected, and a ventilator is required to assist breathing. Kids who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy typically have a life span of about 20 years.

Although most kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy have average intelligence, about one-third of them experience learning disabilities and a small number of them have mental retardation.

While the incidence of Duchenne is known, it's unclear how common other forms of MD are because the symptoms can vary so widely between individuals. In fact, in some people the symptoms are so mild that the disease goes undiagnosed.

Becker muscular dystrophy is similar to Duchenne, but it is less common and progresses more slowly. This form of MD affects approximately 1 in 30,000 boys. It too is caused by insufficient production of dystrophin.

With this form of MD, symptoms typically begin during the teen years, then follow a pattern similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle weakness first begins in the pelvic muscles, then moves into the shoulders and back. Many children with Becker have a normal life span and can lead long, active lives without the use of a wheelchair.

Myotonic dystrophy, also known as Steinert's disease, is the most common adult form of muscular dystrophy, although half of all cases are diagnosed in people who are younger than 20 years old. It is caused by a portion of a particular gene that is larger than it should be. The symptoms can appear at any time during a child's life.

The main symptoms include muscle weakness, myotonia (in which the muscles have trouble relaxing once they contract), and muscle wasting, where the muscles shrink over time. Kids with myotonic dystrophy also can experience cataracts and heart problems.

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy affects boys and girls equally. Typically, symptoms begin when kids are between 8 and 15 years old. This form of MD progresses slowly, affecting the pelvic, shoulder, and back muscles. The severity of muscle weakness varies from person to person. Some kids develop only mild weakness while others develop severe disabilities and as adults need a wheelchair to get around.

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy can affect both boys and girls, and the symptoms usually first appear during the teen years. This form of muscular dystrophy tends to progress slowly.

Muscle weakness first develops in the face, making it difficult for a child to close the eyes, whistle, or puff out the cheeks. The shoulder and back muscles gradually become weak, and kids who are affected have difficulty lifting objects or raising their hands overhead. Over time, the legs and pelvic muscles also may lose strength.

Other types of muscular dystrophy, which are rare, include distal, ocular, oculopharyngeal, and Emery-Dreifuss.

Caring for a Child With Muscular Dystrophy

Though there's no cure for MD yet, doctors are working to improve muscle and joint function, and slow muscle deterioration in kids who are living with the condition.

If your child is diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, a team of medical specialists will work with you and your family. That team will likely include: a neurologist, orthopedist, pulmonologist, physical and occupational therapist, nurse practitioner, cardiologist, registered dietician, and a social worker.

Muscular dystrophy is often degenerative, so kids may pass through different stages as the disease progresses and require different kinds of treatment. During the early stages, physical therapy, joint bracing, and the medication prednisone are often used. During the later stages, doctors may use assistive devices such as:

- physical therapy and bracing to improve your child's flexibility

- power wheelchairs and scooters to improve your child's mobility

- a ventilator to support your child's breathing

- robotics to help your child perform routine daily tasks

Physical Therapy and Bracing

Physical therapy can help a child to maintain muscle tone and reduce the severity of joint contractures with exercises that keep the muscles strong and the joints flexible.

A physical therapist also uses bracing to help prevent joint contractures, a stiffening of the muscles near the joints that can make it harder to move and can lock the joints in painful positions. By providing extra support in just the right places, bracing can extend the time that a child with MD can walk independently.

Prednisone

If a child has Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the doctor may prescribe the steroid prednisone to help slow the rate of muscle deterioration. By doing so, a child with muscular dystrophy may be able to walk longer and live a more active life.

There is some debate over the best time to begin treating a child with prednisone, but most doctors prescribe it when a child with MD is 5 or 6 years old, or when the child's strength begins to show a significant decline. Prednisone does have side effects, though. It can cause weight gain, which can put even greater strain on a child's already-weak muscles. It also can cause a loss of bone density and, possibly, lead to fractures. If your doctor prescribes prednisone, he or she will closely monitor your child.

Spinal Fusion

Many children who have the Duchenne and Becker forms of muscular dystrophy develop severe scoliosis - an S- or C-shaped curvature of the spine that develops when the back muscles are too weak to hold the spine erect. Some kids who have severe cases of scoliosis undergo spinal fusion, a surgery that can reduce pain, lessen the severity of the spine curvature so that a child can sit upright and comfortably in a chair, and ensure that the spine curvature doesn't have an effect on the child's breathing. Typically, spinal fusion surgery only requires a short hospital stay.

Respiratory Care

Many kids with muscular dystrophy also have weakened heart and respiratory muscles. As a result, they can't cough out phlegm and sometimes develop respiratory infections that can quickly become serious. Good general health care and regular vaccinations are especially important for children with muscular dystrophy to help prevent these infections.

Assistive Devices

A variety of new technologies are available to create independence and mobility for kids with muscular dystrophy.

Some kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy may use a manual wheelchair once it becomes difficult to walk. Others go directly to a motorized wheelchair, which can be equipped to meet their needs as muscle deterioration advances.

Robotic technologies also are under development to help kids move their arms and perform activities of daily living.

If your child would benefit from an assistive technological device, it's a good idea to contact your local chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Association (see the Additional Resources tab for a link to their website) to ask about financial assistance that might be available. In some cases, health insurers cover the cost of these devices.

The Search for a Cure

Researchers are quickly learning more about what causes the genetic disorder that leads to muscular dystrophy, and about possible treatments for the disease. If you'd like to know more about the most current research on muscular dystrophy, contact the local chapter of the Muscular Dystrophy Association, or talk to your child's doctor.