Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a deformity of the hip that can occur before, during, or weeks after birth.

At periodic checkups, a doctor will examine your baby's hips to rule out DDH, which can cause hip dislocation and/or an abnormal walk. It's important to recognize DDH early, so a child can receive timely treatment and avoid orthopedic problems later in life.

What Is DDH?

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. In a normal-functioning hip, the rounded top of the thighbone, or femoral head, rests comfortably in the acetabulum (the cup-like hipbone socket).

In mild cases of DDH, the femoral head moves back and forth within the socket, causing a child to have an unstable hip. In more serious cases, the head becomes dislocated, moving completely out of the socket, but sometimes can be put back in with pressure. In the most severe cases, the femoral head may not even reach the socket where it should be held in place.

Hip dislocations are relatively uncommon, affecting just 1 in 1,000 live births. However, some degree of instability of the hip is seen in as many as 1 in 3 newborns. Girls are more likely to develop dislocations of the hip.

What Causes It?

The causes of DDH aren't completely understood, but experts think that many factors are involved. The cramping of the fetus inside the uterus — which is more likely to happen in first pregnancies when the uterus is tight, or in pregnancies where there is a decrease of amniotic fluid (liquid in the womb) — can increase the likelihood of DDH.

Other factors include abnormal positioning of the fetus inside the womb, such as being in the breech position (buttocks face the birth canal), especially when the knees extend out with the feet near the head (called "frank breech"). Having other conditions develop as a result of positioning, like metatarsus adductus (an inward curving of the foot), increases the odds of a child developing DDH.

DDH also may be caused by the infant's response to the mother's hormones that relax the ligaments for labor and delivery, causing the baby's hip to soften and stretch during labor. In 20% of cases, family history is a factor, and if it is, future children should be checked by ultrasound at 6 weeks of age.

Signs and Symptoms

DDH usually affects only one side of the body, most often the right side, and pain is rare.

Infants often don't show signs that they have DDH, and there may be no signs at all. Still, doctors look for these indicators:

- at birth, an inability to move the thigh outward at the hip as far as possible

- an audible "click" during routine post-natal checkups

- different leg lengths

- asymmetry in the fat folds of the thigh around the groin or buttocks

- after 3 months, asymmetry in the motion of the hip and obvious shortening of the affected leg

- in older kids, an exaggeration in the spinal curvature that may develop to compensate for the abnormally developed hip

- limping in older children

Diagnosis

A doctor can determine whether a hip is dislocated or likely to become dislocated by gently pushing and pulling on the child's thighbones, and determining whether they are loose in their sockets. In one commonly used diagnostic test, a child lies on a flat surface and his or her thighs are spread out in order to gauge the hips' range of motion.

A second test brings the knees together and attempts to push the femoral head rearward, out of the socket. It is during these tests that the doctor will hear a "click," which may indicate a dislocation. These maneuvers are done at routine checkups until the baby is walking normally.

Sometimes a doctor will recommend that a child undergo an X-ray or ultrasound to get a better view of a dislocated hip. Ultrasounds are recommended for babies under 4 months of age, while X-rays are performed on older kids. Prior to 4 months of age, hip tissue has not yet hardened (or ossified) from flexible cartilage to bone, and therefore does not show up on X-ray images that capture only bony anatomy and not cartilage.

Treatment

Treatment for DDH depends on the age of the child and the severity of the condition. Mild cases may correct themselves in the first few weeks of life.

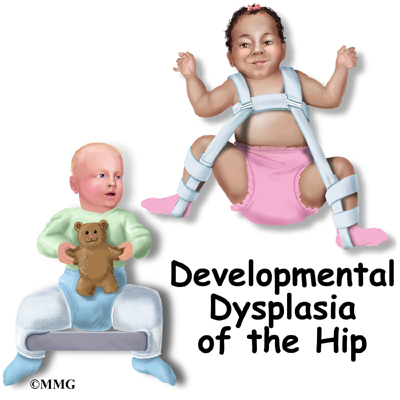

If an unstable hip is seen in newborns, the hip may be held in position with a Pavlik harness. This device keeps the femoral head in its socket by holding the knee up toward the child's head. A shoulder harness attaches to foot stirrups to keep the leg elevated. The goal is to tighten the ligaments in the area and stimulate normal forming of the hip socket. Treatment with the Pavlik harness lasts about 6 to 12 weeks, and continues until the hip is stable and ultrasound exams are normal.

After a child reaches 6 months of age the Pavlik harness will be ineffective. Older kids will need to undergo one of the following treatments:

- Closed reduction. The bone is manually put back into place after the child is put under anesthesia. This treatment is usually preferred in children younger than 18 months.

- Open reduction. The hip is realigned and the thighbone is placed back into the hip socket through surgery. During the procedure, tight muscles and tissues surrounding the hip joint are loosened and then later tightened up once the hip is back in place. This is the procedure of choice for kids older than 18 months.

After reaching age 2 or 3, a child might need surgery on the pelvis to deepen the hip socket (if it's too shallow) or to shorten the thighbone or realign it. Following surgery, the child is put in a hip spica (body cast). About 1 in 20 babies with DDH needs more than the Pavlik harness to correct the condition.

Caring for Your Child

DDH can't be prevented, but if it's recognized early and treated appropriately, most children will develop normally and have no related problems. DDH does not cause pain initially, but if left untreated it can result in significant impairment of function.

Kids with untreated DDH will have legs of uneven lengths in adulthood, which can lead to a limp or waddling gait, back and hip pain, and overall decreased agility.