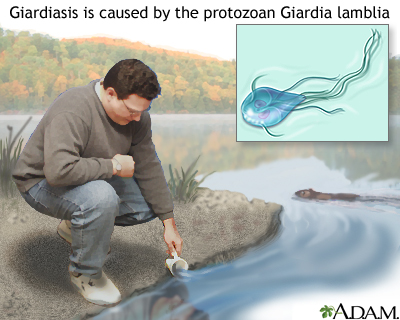

Giardiasis, an illness that affects the digestive tract, is caused by a microscopic parasite called Giardia lamblia. The parasite attaches itself to the lining of the small intestines in humans, where it sabotages the body's absorption of fats and carbohydrates from digested foods.

Giardia is one of the chief causes of diarrhea in the United States, and is transmitted through contaminated water. It can survive the normal amounts of chlorine used to purify community water supplies, and can live for more than 2 months in cold water. As few as 10 of the microscopic parasites in a glass of water can cause a severe case of giardiasis in a human being who drinks it.

Young kids are three times more likely to have giardiasis than adults, which leads some experts to believe that our bodies gradually develop some form of immunity to the parasite as we grow older. But it isn't unusual for an entire family to have giardiasis, with some family members having diarrhea, some just crampy abdominal pains, and others with few or no symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms

It's estimated that between 1% and 20% of the U.S. population has giardiasis, and this figure may be 20% or higher in developing countries, where giardiasis is a major cause of epidemic childhood diarrhea. But more than two thirds of people who are infected may have no signs or symptoms of illness, even though the parasite is living in their intestines.

When the parasite does cause symptoms, the illness usually begins with severe watery diarrhea, without blood or mucus. Giardiasis affects the body's ability to absorb fats from the diet, so the diarrhea contains unabsorbed fats. That means that the diarrhea floats, is shiny, and smells very bad.

Other symptoms include:

- abdominal cramps

- large amounts of intestinal gas

- an enlarged belly from the gas

- loss of appetite

- nausea and vomiting

- sometimes a low-grade fever

These symptoms may last for 5 to 7 days or longer. If they last longer, a child may lose weight or show other signs of poor nutrition.

Sometimes, after acute (or short-term) symptoms of giardiasis pass, the disease begins a chronic (or more prolonged) phase.

Symptoms of chronic giardiasis include:

- periods of intestinal gas

- abdominal pain in the area above the navel

- poorly formed, "mushy" bowel movements (poop)

Prevention

Here are some ways to protect your family from giardiasis:

- Drink only from water supplies that have been approved by local health authorities.

- Bring your own water when you go camping or hiking, instead of drinking from sources like mountain streams.

- Wash raw fruits and vegetables well before you eat them.

- Wash your hands well before you cook food for yourself or for your family.

- Encourage your kids to wash their hands after every trip to the bathroom and especially before eating. If someone in your family has giardiasis, wash your hands often as you care for him or her.

- Have your kids wash their hands well after handling anything in "touch tanks" in aquariums, a potential source of giardiasis.

- Have your water checked on a regular basis if it comes from a well.

Also, it's questionable whether infants and toddlers still in diapers should be sharing public pools. But certainly they should not if they're having diarrhea or loose stools (poop).

Contagiousness

People and animals (mainly dogs and beavers) who have giardiasis can pass the parasite in their stool. The stool can then contaminate public water supplies, community swimming pools, and "natural" water sources like mountain streams. Uncooked foods that have been rinsed in contaminated water may also spread the infection.

In child-care centers or any facility caring for a group of people, giardiasis can easily pass from person to person. At home, an infected family dog with diarrhea may pass the parasite to human family members who take care of the sick animal.

Diagnosis

Doctors confirm the diagnosis of giardiasis by taking stool samples and sending them to the lab to be examined for Giardia parasites. Several samples may be needed before the parasites are found.

For that reason the doctor may order a much more sensitive test called the Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay or ELISA test.

Less often, doctors make the diagnosis by looking at the lining of the small intestine with an instrument called an endoscope and taking samples from inside the intestine to be sent to a laboratory. This is done in more extreme cases, when a definite cause for the diarrhea hasn't been found.

Treatment

Giardiasis is treated with prescription medicines that kill the parasites. Treatment typically takes 5 to 7 days, and the medicine is usually given as a liquid that your child can drink. Some of these medicines may have side effects, so your doctor will tell you what to watch for.

If your child has giardiasis and your doctor has prescribed medication, be sure to give all doses on schedule for as long as your doctor directs. This will help your child recover faster and will kill parasites that might infect others in your family. Again, encourage all family members to wash their hands frequently, especially after using the bathroom and before eating.

A child who has diarrhea from giardiasis may lose too much fluid in the stool and become dehydrated. Make sure the child drinks plenty of fluids but no caffeinated beverages, because they make the body lose water faster.

Ask the doctor before you give your child any nonprescription drugs for cramps or diarrhea because these medicines may mask symptoms and interfere with treatment.

Duration

The incubation period for giardiasis is 1 to 3 weeks after exposure to the parasite. In most cases, treatment with 5 to 7 days of antiparasitic medication will help kids recover within a week's time. Medication also shortens the time that they're contagious. If giardiasis isn't treated, symptoms can last up to 6 weeks or longer.

When to Call the Doctor

Call the doctor whenever your child has:

- large amounts of diarrhea, especially if he or she also has a fever and/or abdominal pain

- occasional, small episodes of diarrhea that continue for several days, especially if appetite is poor, and your child is either gradually losing weight or isn't gaining as much as expected