Few things are more frightening than finding out your child has a brain tumor. Yet it's a fear many parents have had to face. Brain tumors are now the second most common group of childhood cancers, after leukemia, affecting approximately 2,300 children each year.

Some can be cured relatively easily; others have a poorer outlook. All require a very specialized treatment plan involving a team of medical specialists, and all are likely to take a tremendous physical and emotional toll on the kids and their families.

What Is a Brain Tumor?

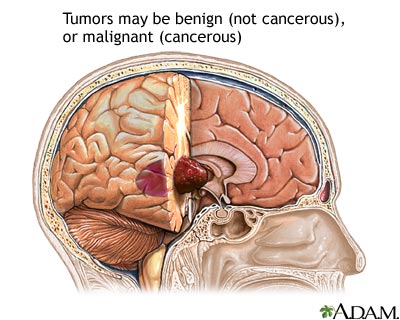

A tumor is any mass caused by abnormal or uncontrolled growth of cells. Tumors in the brain are categorized according to several factors, including where they're located, the type of cells involved, and how quickly they're growing.

Medical terms doctors may use to describe brain tumors include:

- Primary vs. secondary: Primary brain tumors originate in the brain. Secondary brain tumors are made up of cells that have spread (metastasized) to the brain from somewhere else in the body. In children, most brain tumors are primary. The opposite is true in adults.

- Benign vs. malignant: Benign tumors are slow-growing, noncancerous, and do not spread to surrounding tissue. Malignant tumors, on the other hand, are cancerous. Fast-growing and aggressive, they can invade nearby tissue and also are more likely to recur after treatment. Though malignancies are generally associated with a worse outlook, in the brain, benign tumors can be just as serious, especially if they're in a critical location (such as the brain stem, which controls breathing) or grow large enough to press on vital brain structures.

- Localized vs. invasive: A localized tumor is confined to one area and is generally easier to remove, as long as it's in an accessible part of the brain. An invasive tumor has spread to surrounding areas and is more difficult to remove completely.

- Grade: The grade of a tumor indicates how aggressive it is. Today, most medical experts use a system designed by the World Health Organization (WHO) to identify brain tumors and help make a prognosis. The lower the grade, the less aggressive the tumor and the greater the chance for a cure. The higher the grade, the more aggressive the tumor and the harder it may be to cure.

What Causes a Brain Tumor?

Most brain tumors in children originate when a normal cell begins to grow abnormally and reproduce too rapidly. Eventually these cells develop into a mass called a tumor. The exact cause of this abnormal growth is unknown, though research continues on possible genetic and environmental causes.

Some kids are more susceptible to developing brain tumors due to certain genetic conditions. Diseases such as neurofibromatosis, von Hippel-Lindau disease, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, and retinoblastoma are all associated with a higher risk of brain tumors.

Signs and Symptoms

A brain tumor can cause symptoms in a number of ways: by directly destroying brain cells, by causing swelling at the tumor site, by causing a buildup of fluid in the brain (hydrocephalus), and by increasing pressure within the skull. A range of symptoms can develop as a result.

Signs or symptoms vary depending on a child's age and the location of the tumor, but may include:

- seizures

- weakness of the face, trunk, arms, or legs

- slurred speech

- difficulty standing or walking

- poor coordination

- headache

- in babies, a rapidly enlarging head

Because early warning signs can be gradual and may mimic those of other common childhood conditions, brain tumors can be difficult to diagnose. So it's always wise to discuss any symptoms that concern you with your child's doctor.

Diagnosis

A doctor who suspects that a child has a brain tumor will order imaging studies of the brain: a CT scan or MRI, possibly both. These procedures let doctors see inside the brain and pinpoint the area of the tumor. Although both are painless, they do require children to be very still. Kids usually don't require sedation for CT scans, which can be done fairly quickly. Most, however, do need to be sedated for an MRI scan.

If imaging studies reveal a brain tumor, then surgery is likely to be the next step. A pediatric neurosurgeon will try to remove the tumor; if complete removal is not possible, then partial removal — or at least a biopsy (removal of a sample for microscopic examination) — may be done to confirm the diagnosis.

A pediatric pathologist (a doctor who helps diagnose diseases in children by looking at body tissues and cells under a microscope) and a neuropathologist (a pathologist who specializes in diseases of the nervous system) then review the tissue to classify and grade the tumor.

Special tests such as karyotyping, PCR, FISH, and gene expression profiling might be used to analyze the genetic makeup of the tumor cells. Using these tests to get specific information about cancer cells helps doctors develop the best treatment plan for someone with a brain tumor.

Treatment

Most pediatric brain tumor patients require treatment with some combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Advancements in all three areas have contributed to better outcomes over the last few decades.

The care of a child with a brain tumor is very complicated and requires close coordination between many members of a medical team. Members of this team typically include:

- a pediatric neuro-oncologist (a doctor who specializes in treating cancers of the brain or spine)

- a pediatric neurologist (a doctor who specializes in disorders of the nervous system)

- a pediatric neurosurgeon (a surgeon who operates on the brain or spine)

- a radiation therapist (a specialist who administers radiation therapy)

- rehabilitation medicine specialists, including speech, physical, and occupational therapists

- psychologists and social workers

These experts must choose a child's therapy very carefully because the potential for long-term effects, particularly from radiation, is high. (Radiation therapy, though often effective, can cause injury to the developing brain, especially in younger patients.) Striking the delicate balance between giving just enough therapy to cure the child, but not so much as to damage healthy cells and cause unnecessary side effects, is probably the most difficult aspect of treating brain tumors.

Surgery

Surgeons are having more success than ever removing brain tumors, partly because of new technologies in the operating room — especially those that allow real-time images of the brain to guide surgeons as they operate. These include stereotactic devices, which help target tumors by providing 3D images of the brain; intraoperative MRI, which lets doctors see beyond what is exposed during surgery and more clearly distinguish the boundary between tumor and healthy tissue; and other image-guidance systems that allow for more precise navigation.

Staged surgeries are also being used more frequently. That means that instead of trying to remove a large tumor all at once, surgeons will take a small part, and then attempt to shrink the tumor with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. After several months of treatment, the surgeon may go back a second or even a third time to totally remove the rest of the tumor.

After surgery, some tumors may not require any more treatment beyond observation (periodic checkups and imaging scans to watch for trouble). Many, however, require more aggressive therapies, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of both.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy — the use of high-energy light to kill rapidly dividing cells — is very effective in the treatment of many pediatric brain tumors. However, because the developing brain in children younger than 10 (and especially younger than 5) is highly sensitive to its effects, radiation therapy can have serious long-term consequences. These may include seizures, stroke, developmental delays, learning problems, growth problems, and hormone problems.

As with surgery, the delivery of radiation therapy has changed significantly over the last decade. New computer-assisted technologies have allowed doctors to construct 3D radiation fields that accurately target tumor tissue, while avoiding critical brain structures, such as the hearing centers. Still, the advantages and disadvantages of using radiation therapy should always be discussed with your doctor.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy is often administered through a special long-lasting intravenous (IV) catheter called a central line, and may require frequent hospital stays. Although chemotherapy has many short-term side effects (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, etc.), it has fewer long-term side effects than radiation therapy. Many children with brain tumors are treated with chemotherapy in order to delay or avoid radiation treatment.

Unlike brain tumors in adults, many pediatric brain tumors are highly sensitive to the effects of chemotherapy and respond well to high doses of it. However, giving a child high-dose chemotherapy can cause serious damage to the bone marrow (the spongy material inside bones that produces blood cells).

To prevent bone marrow damage from becoming permanent, a procedure called "stem-cell rescue" may be done. The patient's own bone marrow or blood stem cells are collected and stored until after the high-dose chemotherapy is completed. Then the marrow or stem cells are infused back into the patient to help the damaged bone marrow recover.

Common Types of Brain Tumors

There are many different types of pediatric brain tumors, ranging from those that can be cured with minimal therapy to those that cannot be cured even with aggressive therapy.

Some of the most common types are:

Astrocytomas

Astrocytomas come in four major subtypes: juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma (grade 1), fibrillary astrocytoma (grade 2), anaplastic astrocytoma (grade 3), and glioblastoma multiforme (grade 4). The higher the grade, the more aggressive the tumor.

Another important feature of astrocytomas is location, because where the tumor is directly affects the chance for a cure. For example, astrocytomas in the cerebrum and cerebellum tend to be low grade and located closer to the brain's surface, and so often can be treated with surgery alone. Optic pathway gliomas (which occur near the eyes) and astrocytomas (in the central parts of the brain) cannot be easily removed and often require a longer, more complex treatment approach.

Ependymomas

When located in the top part of the brain, these tumors often can be cured by surgery alone. However, when located in the center or back portion of the brain, they usually require much more aggressive therapy and can be difficult to cure.

Brain Stem Gliomas

Diffuse pontine gliomas, the most common subtype of brain stem gliomas, are located in a part of the brain that does not tolerate surgery. Patients with brain stem gliomas typically are treated with radiation therapy alone, although both surgery and chemotherapy have been used, with little success. Long-term survival rates are low for children with these tumors.

Medulloblastomas and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors (PNETs)

These related tumors, which are identical under the microscope, differ primarily in their location. Medulloblastomas are located in the back part of the brain, near the brain stem, while PNETs can be located anywhere else in the brain. Both tumors require aggressive therapy, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Although these are dangerous cancers and the treatments are intense, cure rates are improving every decade. In fact, the majority of children with these types of tumors can now be cured.

Craniopharyngiomas

These rare, benign tumors are slow-growing. Although they do not spread, they can cause serious problems by putting pressure on critical brain structures. Treatment typically involves surgery and radiation, although in some cases surgery alone is used. Long-term survival is excellent.

Germ Cell Tumors

These tumors usually arise from two special areas in the midline of the brain, the area around the pituitary gland and the pineal gland. They can be difficult to treat, but a cure is often possible with aggressive surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Germinomas, the most common type of germ cell tumor, can be treated with either radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both depending on the circumstances.

Late Effects

"Late effects" are problems that patients can develop after cancer treatments have ended. For survivors of pediatric brain tumors, late effects may include cognitive delay, seizures, growth abnormalities, hormone deficiencies, visual and auditory problems, and the possibility of developing a second cancer, including a second brain tumor. Because these problems sometimes don't become apparent until years after treatment, careful observation and regular screenings are needed to catch them as early as possible.

In some cases, short-term effects may improve with the help of physical, occupational, or speech therapy and may continue to improve as the brain heals. In other cases, kids may experience side effects that are longer term, including learning disabilities; medical problems such as diabetes, growth delay, or delayed or early puberty; physical disabilities related to movement, speech, or swallowing; and emotional problems linked to the stresses of diagnosis and treatment.

Be aware of the potential for physical and psychological late effects, especially when the time comes for your child to return to school, activities, and friendships. Talk to teachers about the impact treatment has had on your child and discuss any accommodations that may need to be made, including a limited schedule, additional rest time or bathroom visits, modifications in homework, testing or recess activities, and medication scheduling. Your doctor can offer advice on how to make the transition easier.

Caring for Your Child

Parents often struggle with how much to tell a child who is diagnosed with a brain tumor. Though there's no one-size-fits-all answer for this, experts do agree that it's best to be honest — but to tailor the details to your child's degree of understanding and emotional maturity.

Give as much information as your child requires, but not more. And when explaining treatment, try to break it down into steps. Addressing each part as it comes — visiting various doctors, having a special machine take pictures of the brain, needing an operation — can make the big picture less overwhelming.

Kids should be reassured that the brain tumor is not the result of anything they did, and that it's OK to be angry or sad. Really listen to your child's fears, and when you feel alone, seek support. Your hospital's social workers can put you in touch with other families of children with brain tumors who've been there and may have insights to share.

Also be aware that it's common for siblings to feel neglected, jealous, and angry when a child is seriously ill. Explain as much as they can understand, and enlist family members, teachers, and friends to help keep some sense of normalcy for them. And finally, as hard as it may be, try to take care of yourself. Parents who get the support they need are better able to support their child.