While you were anticipating your new baby, you probably mentally prepared yourself for the messier aspects of child rearing: poopy diapers, food stains, and of course, spit up. But what's normal and what's not when it comes to spitting up or vomiting in infants?

While you were anticipating your new baby, you probably mentally prepared yourself for the messier aspects of child rearing: poopy diapers, food stains, and of course, spit up. But what's normal and what's not when it comes to spitting up or vomiting in infants? Pyloric stenosis, a condition that affects the gastrointestinal tract during infancy, isn't normal - it can cause your baby to vomit forcefully and often and may cause other problems such as dehydration and salt and fluid imbalances. Keep reading to understand why getting immediate treatment for pyloric stenosis is so important.

What Is Pyloric Stenosis?

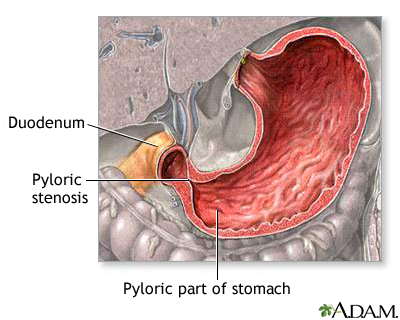

Pyloric stenosis is a narrowing of the pylorus, the lower part of the stomach through which food and other stomach contents pass to enter the small intestine. When an infant has pyloric stenosis, the muscles in the pylorus have become enlarged to the point where food is prevented from emptying out of the stomach.

Also called infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis or gastric outlet obstruction, pyloric stenosis is fairly common - it affects about three out of 1,000 babies in the United States. Pyloric stenosis is about four times more likely to occur in firstborn male infants. It has also been shown to run in families - if a parent had pyloric stenosis, then an infant has up to a 20% risk of developing the condition. Pyloric stenosis occurs more commonly in Caucasian infants than in babies of other ethnic backgrounds, and affected infants are more likely to have blood type B or O.

Most infants who develop pyloric stenosis are usually between 2 weeks and 2 months of age - symptoms usually appear during or after the third week of life. It is one of the more common causes of intestinal obstruction during infancy that requires surgery.

What Causes Pyloric Stenosis?

It is believed that babies who develop the condition are not born with pyloric stenosis, but that the progressive thickening of the pylorus occurs after birth. An affected infant begins showing symptoms when the pylorus is so thickened that the stomach can no longer empty properly.

It is not known exactly what causes the thickening of the muscles of the pylorus - it may be a combination of several factors. Some researchers believe that maternal hormones could be a contributing cause. Others believe that the thickening of the muscle is the stomach's response to some type of allergic reaction in the body.

Some scientists believe that babies with pyloric stenosis lack receptors in the pyloric muscle that detect nitric oxide, a chemical in the body that tells the pylorus muscle to relax. As a result, the muscle is in a state of contraction almost continually, which causes it to become larger and thicker over time. It may take some time for this thickening to occur, which is why pyloric stenosis usually appears in babies a few weeks after birth.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of pyloric stenosis generally begin around 3 weeks of age. They include:

- Vomiting - The first symptom of pyloric stenosis is usually vomiting. At first it may seem that the baby is simply spitting up frequently, but then it tends to progress to projectile vomiting, in which the breast milk or formula is ejected forcefully from the mouth, in an arc, sometimes over a distance of several feet. Projectile vomiting usually takes place soon after the end of a feeding, although in some cases it may be delayed for hours. Rarely, the vomit may contain blood.

In some cases, the vomited milk may smell curdled because it has mixed with stomach acid. The vomit will not contain bile, a greenish fluid from the liver that mixes with digested food after it leaves the stomach.

Despite vomiting, a baby with pyloric stenosis is usually hungry again soon after vomiting and will want to eat. The symptoms of pyloric stenosis can be deceptive because even though a baby may seem uncomfortable, he may not appear to be in great pain or at first look very ill.

- Changes in stools - Babies with pyloric stenosis usually have fewer, smaller stools because little or no food is reaching the intestines. Constipation or stools that have mucus in them may also be symptoms.

- Failure to gain weight and lethargy - Most babies with pyloric stenosis will fail to gain weight or will lose weight. As the condition worsens, they are at risk for developing fluid and salt abnormalities and becoming dehydrated.

Dehydrated infants are lethargic and less active than usual, and they will develop a sunken "soft spot" on their heads, sunken eyes, and a doughy, softened, or wrinkled appearance of the skin on the belly and upper parts of the arms and legs. Because urine output is decreased, it may be more than 4 to 6 hours between wet diapers.

After feeds, increased stomach contractions may make noticeable ripples, or waves of peristalsis, which move from left to right over the infant's belly as the stomach tries to empty itself against the thickened pylorus.

It's important to talk to your child's doctor if your baby experiences any of these symptoms.

Other conditions can have similar symptoms as pyloric stenosis. For instance, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) usually begins before 8 weeks of age, with excess spitting up, or reflux - which may resemble vomiting - taking place after feedings. However, most infants with GERD do not experience projectile vomiting, and although they may have poor weight gain, they tend to have normal stools.

In infants, symptoms of gastroenteritis - inflammation in the digestive tract that can be caused by viral or bacterial infection - may also somewhat resemble pyloric stenosis. Vomiting and dehydration are seen with both conditions; however, infants with gastroenteritis usually also have diarrhea with loose, watery, or sometimes bloody stools. Diarrhea usually isn't seen with pyloric stenosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Your child's doctor will ask detailed questions about the baby's feeding and vomiting patterns, including the appearance of the vomit. The most important part of diagnosing pyloric stenosis is a reliable and consistent history and description of the vomiting.

The baby will be fully examined, and any weight loss or failure to maintain growth since birth will be noted. During the exam, the doctor will attempt to feel if there is a pyloric mass - a firm, movable lump that feels like an olive and is sometimes detected in the belly of an infant with pyloric stenosis. If the doctor feels this mass, it's a strong indication that the baby has pyloric stenosis; the baby will be referred to a pediatric surgeon and hospitalized for further treatment.

If the baby's feeding history and physical examination suggest pyloric stenosis but no "olive" is felt, then an ultrasound of the baby's abdomen will usually be performed. The enlarged, thickened pylorus can be seen on ultrasound images.

Sometimes instead of an ultrasound, a barium swallow is performed. The baby swallows a small amount of a chalky liquid (barium), and then special X-rays are taken to view the pyloric region of the stomach to see if there is any narrowing or obstruction.

Infants suspected of having pyloric stenosis usually undergo blood tests because the continuous vomiting of stomach acid, as well as the resulting dehydration from fluid losses, can cause salt (electrolyte) imbalances in the blood that need to be corrected.

When an infant is diagnosed with pyloric stenosis, either through physical examination, ultrasound, or barium swallow, the baby will be admitted to the hospital and prepared for surgery. Any dehydration or electrolyte problems in the blood will be corrected with intravenous (IV) fluids, usually within 24 hours.

A surgical procedure called pyloromyotomy, which involves cutting through the thickened muscles of the pylorus, is performed to relieve the obstruction from pyloric stenosis. The pylorus is examined through a very small incision, and the muscles that are overgrown and thickened are spread. Nothing is cut out - the stitches are under the skin and there are no stitches or clips to remove.

After surgery, most babies are able to return to normal feedings fairly quickly. The baby starts feeding again 3 to 4 hours after the surgery, and the baby can return to breast-feeding or the formula that he was on prior to the surgery. Because of swelling at the surgery site, the baby may still vomit small amounts for a day or so after surgery. As long as there are no complications, most babies who have undergone pyloromyotomy can return to a normal feeding schedule and be sent home within 48 hours of the surgery.

If you are breast-feeding, you may be concerned about being able to continue feeding while your baby is hospitalized. The hospital should be able to provide you with a breast pump and assist you in its use so that you can continue to express milk until your baby can once again feed regularly.

After a successful pyloromyotomy, your infant will not need to follow any special feeding schedules. Your child's doctor will probably want to examine your child at a follow-up appointment to make sure the surgical site is healing properly and that your infant is feeding well and maintaining or gaining weight.

Pyloric stenosis should not recur after a complete pyloromyotomy. If your baby continues to display symptoms weeks after the surgery, it may suggest another medical problem, such as inflammation of the stomach (gastritis) or GERD - or it could indicate that the initial pyloromyotomy was incomplete.

When to Call Your Child's Doctor

Pyloric stenosis is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment. Call your child's doctor if your baby has any of the following symptoms:

- persistent or projectile vomiting after feeding

- poor weight gain or weight loss

- decreased activity or lethargy

- few or no stools over a period of 1 or 2 days

- signs of dehydration such as decreased urination (more than 4 to 6 hours between wet diapers); wrinkly or doughy appearance of the skin on the arms, legs, or belly; sunken "soft spot" on the head; sunken eyes; or jaundice (yellowing of the skin)